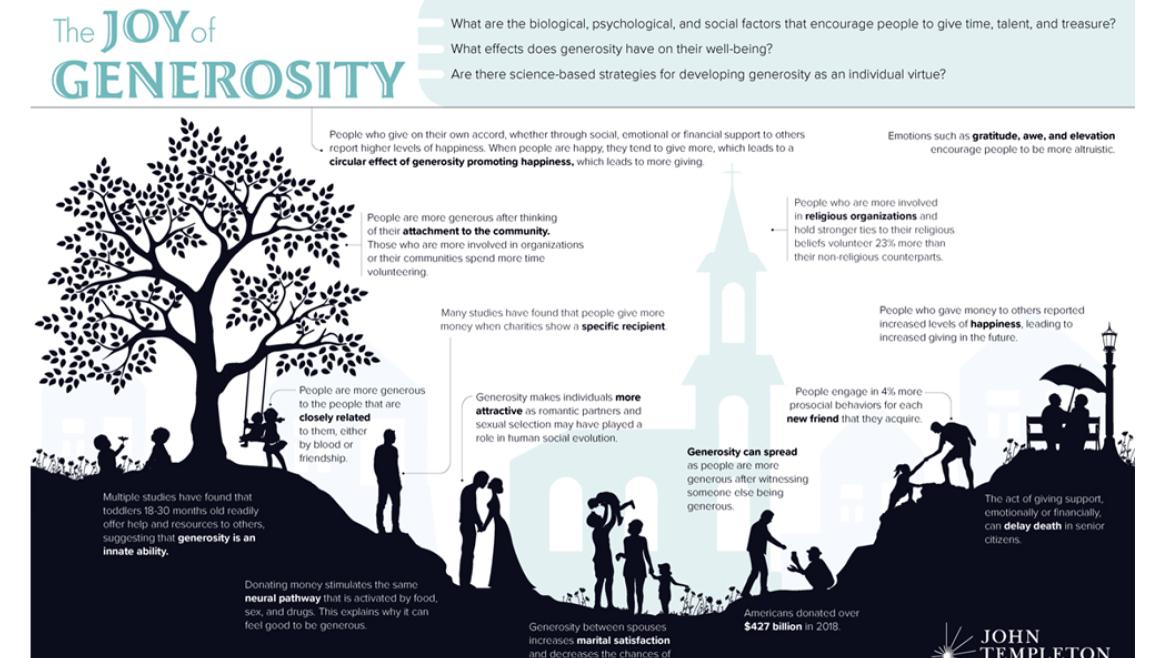

People demonstrate generosity in myriad ways, from gifts of time and money to everyday acts of kindness toward loved ones—and even to deeds that involve substantial self-sacrifice, like donating a kidney to a stranger. But we are often nowhere near as generous as we could (or even aspire to) be. In short: although we have the capacity to be generous, we don’t always act generously. The Science of Generosity poses multiple questions. What are the biological, psychological, and social factors that encourage people to give time, money, and assistance? What effects does such generous behavior have on their well-being? What accounts for differences in individual levels of generosity—and what methods might encourage individuals to give more? Are there evidence-based strategies for cultivating greater degrees of generosity? Such questions have given rise to numerous studies, the results of which are described in a report commissioned by the John Templeton Foundation. The document provides a high-altitude overview of more than 350 studies and meta-studies published in nearly 200 refereed publications between 1971 and 2017.